I’m several years into my career as an engineering manager, and over that time I’ve struggled to measure the value middle managers provide. What follows is an attempt at a framework to do exactly that.

But first, some setup.

Different languages

If you’ve ever heard someone in a leadership role speak, you’ve probably scratched your head or frowned disapprovingly at the volume of empty-sounding buzz words. You might even feel like leaders at your company have a knack for saying a lot of words without actually communicating anything — a feeling I used to have myself.

Conversely, if you’re a seasoned leader, you might grow exasperated with individual contributors that let the details get in the way of the bigger picture.

The problem is that people at a company speak different languages, even within the same discipline. An engineering manager will speak with a slightly different dialect than an engineer on her team. The further you move apart in title or in discipline, the more noticeable the difference between dialects becomes. A leader in the marketing world will hardly be able to understand the rumblings of an infrastructure engineer, and vice versa.

Layers of abstraction

Over time I’ve come to realize that these language differences, especially within a single discipline, stem from people using different degrees of abstraction.

If you’re an engineer that actively codes, you think in terms of the code itself and you understand all of its nuances. In short, you use very little abstraction[1].

But as you move up the chain, you start to take shortcuts that allow you to reason about something without having worked on or even seen the underlying code. You build mental models. You reduce the number of “boxes” when representing how a system works.

The higher you go, the less granular your mental models, the fewer boxes in your diagrams, etc.

All of this is by necessity: as your scope increases to cover an entire team, division, or organization, it’s impossible to maintain the same level of understanding you had when you were the one doing the work yourself. To be effective at all, you have to use progressively more layers of abstraction as your scope grows.

The Abstraction Spectrum

We can formalize that idea into an actual spectrum: the abstraction spectrum.

Imagine there was some discipline-specific measurement of how much or how little abstraction someone uses in their work. For engineers, that might be how many boxes they use when drawing a system diagram, or how many steps they show in a sequence diagram, etc. For a different discipline, perhaps it’s the number of steps used to describe a process or the number of words used to describe a product. The exact measurement doesn’t matter.

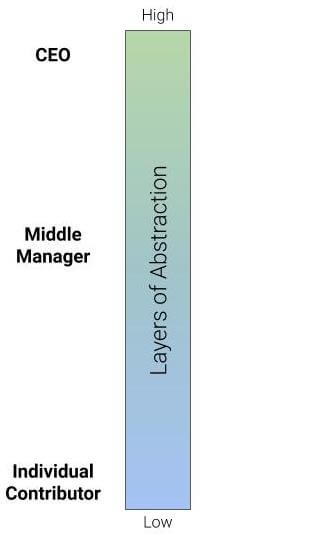

In this imaginary situation, you could then record everyone’s position in the company against how many layers of abstraction they use. What you’d find is that — on average — the two are strongly correlated: the higher up in a company, the more abstraction you use. It might look something like this:

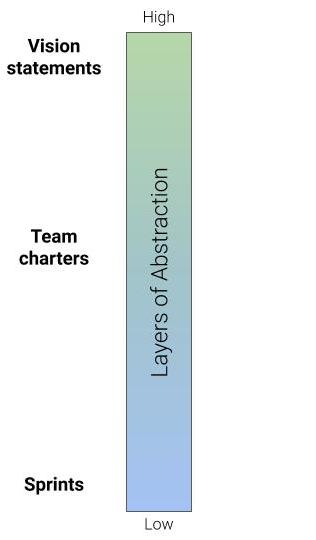

Alternatively, we can map that spectrum to the typical language you might find at each level:

The Translation Spectrum

With that context in mind, we can finally take a stab at defining the value a middle manager provides:

The value of middle managers is proportional to how much of the Abstraction Spectrum they can efficiently navigate.

Visually, that looks like this:

TODO: Insert two diagrams side by side that highlight a large area vs a small area for a good vs bad manager

Why does the size of the translation spectrum matter?

Simple: abstractions are powerful, but potentially dangerous. More explicitly, the wrong abstraction is dangerous. If someone has an incorrect or incomplete mental model of how something works, they might make the wrong decision.

TODO: Provide an example (maybe medical field?) where a reasonable sounding analogy could lead you to a bad decision

Middle managers who can navigate more levels of abstraction can make sure the right abstractions are being made up the chain. They facilitate the flow of information through a company by translating faithfully across levels of abstraction.

The Translation Spectrum in 2D

We can add a second dimension to our translation spectrum to account for discipline.

TODO: Insert diagram that shows graduations by level on a vertical “level of abstraction” line and extends horizontally with color coded discipline zones

This gives a more nuanced and accurate perspective on a middle manager’s value. It’s not just how many layers of abstraction they comfortably span, but also how well they interface with other disciplines. A manager that knows how to translate between marketing, engineering, and analytics is much more valuable than a manager that only knows how to interface with marketing.

TODO: Draw a grid that outlines what a big company’s key roles might look like: CEO spans entire horizontal but only shallowly, CMO goes deep in marketing

Note: One thing that makes Elon Musk so abnormal is that he spans a ridiculous portion of the translation spectrum: as a CEO of not one but two massive companies, he still engages at the lowest levels of abstraction.