This was not how they taught me about finances.

This was not how they taught me about finances.

It’s an unfortunate fact that we overlook personal finance in today’s education system. We spend months learning about Italian renaissance painters (no offense da Vinci), but rarely hear a word about how to avoid credit card debt or save for retirement.

If you haven’t checked the internet recently, allow me to briefly recap the state of personal finance in the US: the average millennial has a savings rate of negative 2 percent, student loan debt has increased over 50% over the last ten years and is now over $1.5 trillion, and those nearing retirement have massive shortfalls in their savings.

So yeah, it isn’t pretty.

Luckily for me, my parents started teaching me about finances at a young age. That helped me save and invest smartly throughout my teenage and adult years, and put me on a healthy financial track. I’m forever grateful to them for their help.

Teaching your kids (or future kids) about finances is one of the best ways to positively shape their future. What follows is the story of how my parents did that for me.

Since they started when I was five years old, my parents kept things simple. They focused on instilling two important lessons:

- Hard work pays off.

- Money can work for you.

The setup

My parents used a pegboard to track our chores.

I had a list of mandatory chores, like doing my homework, feeding our dog, cleaning the dishes, etc. Apparently, brushing my teeth was also a chore. I did those chores free of charge, because I’m cool like that.

Then there was the bonus list. That list included things like taking out the garbage, picking up dog poop, folding clothes, etc. Each peg from the bonus list was worth $0.10.

As my mom relayed over text:

You would power through that list and earn all of the pegs. Your brother would complain so you would leave him a couple but he never wanted the dirty chores.

That bonus list didn’t even know what hit it.

Every time you completed a chore, you would take the peg for that chore and put it on your pegboard.

The settle up

At the end of every week, we would sit down as a family and get paid for the chores we did, represented by pegs on our pegboard. My paydays were routinely the largest of my siblings (see above).

In later years, it became a more competitive marketplace; I had to start hustling to do the chores on the bonus list. That’s right, I used to fight with my sister about who got to pick up the dog poop.

Hard work pays off? Check.

The bank accounts

Once we had those paychecks in hand, we would get to decide how to allocate our money. We had three options: a spending account, a savings account, and charity.

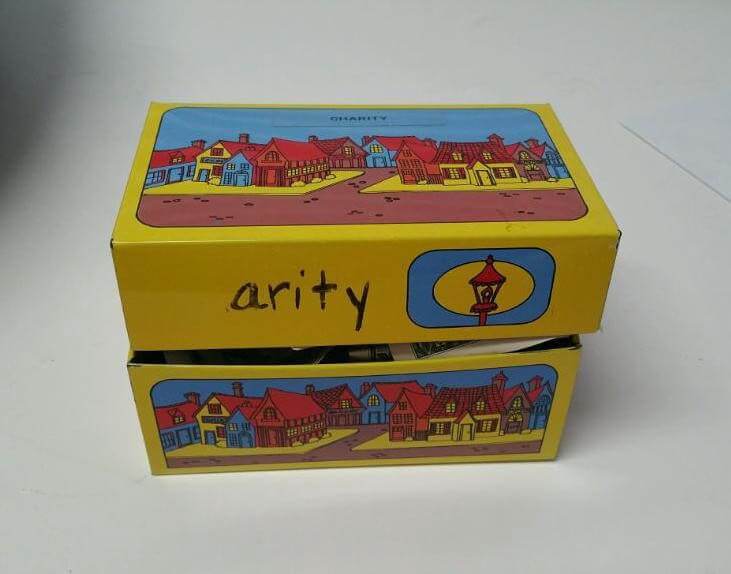

The “accounts” were fake — nothing more than ledgers kept on an index card. We stored the ledger and the cash balance in small notecard boxes.

The charity “account.”

The charity “account.”

We were required to put at least 10% of our money towards charity to help us build that muscle early. The rest went into our spending or savings “accounts.”

If I put my money into my spending account, I could spend it that week when we were shopping, or — more than likely — when I wanted to splurge on candy in the grocery store.

If I put it into my savings account, I couldn’t touch it until the following week when we went through this exercise again. Here’s the most important part, though: the savings account accrued interest every week.

When I viewed my balance at the end of the week, I would see that money had been added to my savings account without me having to do anything!

Keep in mind: I was five years old. I didn’t know that money could do that. Money could make more money if you didn’t spend it? That’s magic ✨

The interest rate was higher than anything you’d find in the real world, but the lesson was learned. Saving your money pays dividends, literally and figuratively.

I doubled down on doing chores and moved as much money as I could from my checking account to my savings account after that.

Money can work for you? Check.

Transitioning to the real deal

There were some other valuable lessons that came out of that weekly payday session.

For example, I learned how to balance the ledger on that index card. If I moved $4 from my checking account to my savings account, I would write down -$4 on the checking ledger and +$4 on the savings ledger. If I spent $6 at the store, I would keep track of it just like I would if I had been balancing a checkbook.

Having internalized the fundamentals, it was time for the big leagues. My parents opened a joint bank account with me. I moved my money to a real bank and put it into real checking and savings accounts.

Expanding from there

Opening that account taught me that real interest rates weren’t as wonderful as the one my parents had been giving me.

It was a sad moment, but my parents used it to teach me another valuable lesson: there’s more to investing than just putting your money into a savings account.

And with that, they introduced me to the stock market.

They started by explaining that any time you buy stock, you’re actually buying a small piece of that company. At the time, I thought that was the coolest thing since fruit rollups which, given my age, was pretty freakin cool: I could own part of a company! Magic ✨

I distinctly remember buying my first two shares of Intel for just over $100 each when I was eleven years old. It went through a 2-for-1 split shortly after that, and the rest was history: I was hooked.

Up, up and away

By the time I entered high school, I knew more about balancing a checkbook, saving, investing, and the common pitfalls of credit cards than most recent college grads did, let alone my classmates.

Looking back, it’s painfully obvious that none of this would have been possible without the important lessons my parents taught me while I was young. Instilling a strong understanding of the basics is one of the best ways parents can ensure their children are financially healthy later in life.

Not everyone will respond well to the methods my parents used, but there are plenty of other ways to get kids interested at a young age. You can create paper trading accounts to spark interest in investing or use app-connected piggy banks to teach them about starting small and setting goals. Nowadays, the only thing stopping you from getting kids interested is a bit of imagination.

For me, my parents’ methods seemed to work out pretty well: I went on to co-found Penny, an easy to use personal finance app that was acquired by Credit Karma in 2018.